Last internal combustion vehicle must be sold by 2038 to achieve net-zero global fleet by 2050; urgent policy action key, especially on heavy commercial vehicles finds BNEF

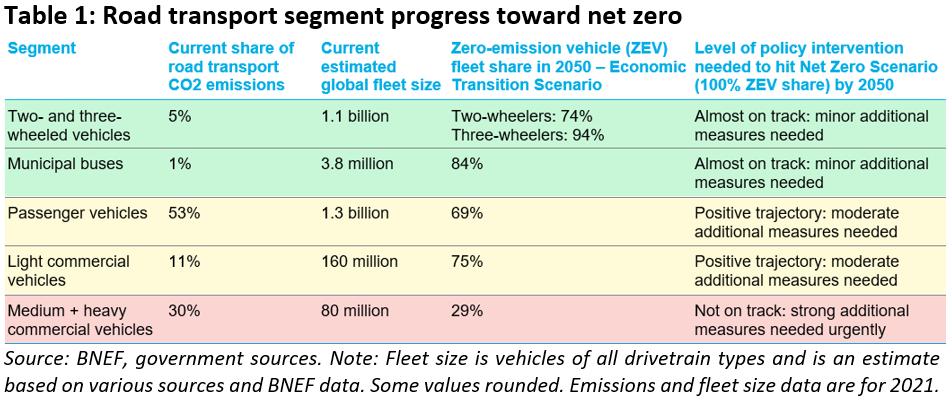

London and New York, June 1, 2022 – The road transport sector can still reach net-zero emissions by 2050 through electrification, but urgent action is required from policymakers and industry participants. Certain segments, such as buses and two- and three-wheelers are close to being on track for net zero, but there is no room for complacency and more action is needed to get on track elsewhere – especially in medium and heavy commercial vehicles.

The Long-Term Electric Vehicle Outlook outlines two scenarios for the uptake of electric transport to 2050, and examines impacts on demand for batteries, materials, oil, electricity, infrastructure and emissions. The Economic Transition Scenario (ETS), which assumes no new policies and regulations are enacted, is primarily driven by techno-economic trends and market forces. The second scenario investigates what a potential route to net-zero emissions looks like for the road transport sector by 2050. This Net Zero Scenario (NZS) looks primarily at economics as the deciding factor for which drivetrain technologies are implemented to hit the 2050 target.

Passenger electric vehicle (EV) sales are set to grow rapidly in the next few years, rising from 6.6 million sold in 2021 to 21 million in 2025. The fleet of EVs on the road hits 77 million by 2025 and 229 million by 2030, based on BNEF’s Economic Transition Scenario. That’s up from 16 million at the end of 2021, and reflective of the remarkable success story of EVs in the energy transition to date.

As EV uptake continues to grow, they are already displacing 1.5 million barrels of oil demand per day. Most of this is from electric two- and three-wheelers in Asia, but rising passenger EV sales push this to 2.5 million barrels per day by 2025. Overall, oil demand from road transport is now set to peak by 2027, according to BNEF’s findings, as electrification spreads to all other areas of road transport beyond passenger cars. Sales of internal combustion engine vehicles already peaked in 2017 and BNEF expects the global fleet of ICE passenger vehicles to start to decline in 2024.

To get on track for a net-zero global fleet by 2050, zero-emission vehicles need to represent 61% of global new passenger vehicle sales by 2030, 93% by 2035, and the last ICE vehicle of any segment needs to be sold by 2038. The report also found that vehicle-to-grid (V2G) technology can play a role in driving down power sector emissions and generating value for consumers.

Colin McKerracher, head of the advanced transport team at BNEF and lead author of the report, said: “Electric vehicles are a powerful tool in reducing global CO2 emissions from the transport sector. There are very positive signs that the market is moving in the right direction, but more action is needed – especially when it comes to heavy trucks. Action also needs to focus on emerging markets, which need financial support to help enable and accelerate the transition to electric mobility of all types.”

According to BNEF, developed countries and multilateral institutions should include electric vehicle investments, incentives and charging infrastructure deployments in their international climate finance plans, making capital available to emerging economies that have credible plans to develop this sector. Concessional finance has been a key enabler for the development of renewable power generation in emerging economies and could play a similar role in the EV sector.

The fleet of passenger electric vehicles is set to hit 469 million in 2035 in the Economic Transition Scenario but needs to jump to 612 million by the same date in the Net Zero Scenario. Much of the gap will have to be met in emerging economies, while wealthy countries should look at ways to support the transition in those markets and avoid a global slowdown of adoption.

Looking at different segments, two- and three-wheelers and buses are already very close to the trajectory needed to achieve BNEF’s NZS. However, medium and heavy commercial vehicles are lagging far behind, and need strong additional policy measures to meet net zero. Under the Economic Transition Scenario, only 29% of these vehicles achieve zero emissions by 2050 – far from the full adoption needed for net zero. In addition to introducing tighter fuel economy or CO2 standards for trucks, governments may need to consider mandates for the electrification of fleets, including those of governments and transport operators. Governments should also consider zero-emissions zones in cites, and incentives to push freight into smaller trucks which can electrify faster than larger ones.

The report also explores whether batteries or fuel cells are the more likely solution for heavy-duty, long-haul freight. By the end of the 2020s, megawatt-scale charging stations, as well as the emergence of higher energy density batteries, will result in battery-electric trucks becoming a viable option for heavy-duty long-haul operations, especially for volume-limited use cases. Direct electrification via batteries appears to be the most economically attractive and efficient approach to decarbonizing road transport, including trucking, and should be pursued wherever possible. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles can help fill the small gaps left by electrification in some heavy vehicles, in regions or duty cycles where batteries struggle.

The report also suggests that reducing car dependence through public transport, walking, cycling and other measures should be pursued wherever possible. A 10% reduction in kilometers travelled by car by 2050 alone would lead to 200 million fewer cars on the road, reducing cumulative CO2 emissions by 2.25 gigatons and alleviating strain on the battery supply chain, all of which will benefit long-term decarbonization targets.

EV manufacturers are contemplating a market for battery raw materials that is very tight for the years ahead. The battery supply chain will require significant near-term investment to avoid a supply crunch. Yet, the rising cost of batteries will not derail near-term EV adoption. Some of the factors that are driving high battery raw material costs – war, inflation, trade friction – are also pushing the price of gasoline and diesel to record highs, which in turn is driving more consumer interest in EVs.